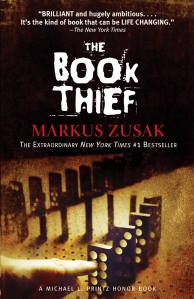

Today I read The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. Among the many awards it has won are the 2006 School Library Journal Best Book of the Year, the 2006 Kirkus Reviews Editor Choice Award, the 2007 ALA Best Books for Young Adults, and the 2007 Michael L. Printz Honor Book award.

Today I read The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. Among the many awards it has won are the 2006 School Library Journal Best Book of the Year, the 2006 Kirkus Reviews Editor Choice Award, the 2007 ALA Best Books for Young Adults, and the 2007 Michael L. Printz Honor Book award.

Death is haunted by humans. He meets every human in the end, no matter how they try to avoid him. So very many humans, and yet a special few he visits more than once, just to watch them. Liesel Meminger is one of the special ones. She is a book thief.

Death sees Liesel steal her first book when he comes for her brother- The Grave Diggers’ Handbook. He finds her again in the small German town of Molching, where she has been adopted by the compassionate housepainter Hans Hubermann and his foul-mouthed wife Rosa. She lives across the street from her best friend Rudy. who tries to steal kisses as they play soccer in the street. And Hitler and his Nazi party are in power far away, but they have eyes everywhere, even in sleepy little Molching. And Liesel steals more books.

Hans is contacted by a Jew, Max Vandenburg, the son of a man who once saved his life. Max needs help hiding from the Nazis, and Hans is an honourable man. He agrees to hide Max in his house, despite the danger-they could all be killed if Max is discovered.

And Liesel steals more books. Any book that she can get her hands on. She learns to read them, and she reads them over and over again. She reads to her neighbours as they hide from bombs. She reads to Max as he lays deathly ill. She reads the stories that Max leaves behind for her. And she reads the words she writes down as her own story- the story of the book thief.

*******************************************************************************

This is a beautiful, lyrical, evocative, difficult, and upsetting novel. I decided to read it because it was a book that I’ve heard recommended quite a few times- I knew vaguely that it was about World War 2, but I wasn’t quite sure what it was about.

Sometimes you come across a book that’s hard to read, emotionally speaking–Jane Yolen’s Briar Rose was another such for me–but you keep on reading it because you know that it will be worth it in the end. Rather like how Bastien kept reading Atreyu’s story in The Neverending Story– sometimes you just can’t give up reading it.

I’ve thought about this book a lot, and I’m still not sure how to describe it other than beautiful and terrible–terrible in the older sense, of extremity–it is a terrible beauty. I absolutely recommend it, though possibly for older grades, around grade 5 and up. This book should be paired with The Diary of Anne Frank for anyone learning about World War 2, because often it’s forgotten that the Germans suffered too. The quote I have following is fairly long, but I think it will give you a better idea of the book than I ever could.

*******************************************************************************

THERE WAS once a strange, small man. He decided three important details about his life:

1. He would part his hair from the opposite side to everyone else.

2. He would make himself a small, strange mustache.

3. He would one day rule the world.

The young man wandered around for quite some time, thinking, planning, and figuring out exactly how to make the world his. Then one day, out of nowhere, it struck him—the perfect plan. He’d seen a mother walking with her child. At one point, she admonished the small boy, until finally, he began to cry. Within a few minutes, she spoke very softly to him, after which he was soothed and even smiled.

The young man rushed to the woman and embraced her. “Words!” He grinned.

“What?”

But there was no reply. He was already gone.

Yes, the Führer decided that he would rule the world with words. “I will never fire a gun,” he devised. “I will not have to.” Still, he was not rash. Let’s allow him at least that much. He was not a stupid man at all. His first plan of attack was to plant the words in as many areas of his homeland as possible.

He planted them day and night, and cultivated them.

He watched them grow, until eventually, great forests of words had risen throughout Germany…. It was a nation of farmed thoughts.

While the words were growing, our young Führer also planted seeds to create symbols, and these, too, were well on their way to full bloom. Now the time had come. The Führer was ready.

He invited his people toward his own glorious heart, beckoning them with his finest, ugliest words, handpicked from his forests. And the people came.

They were all placed on a conveyor belt and run through a rampant machine that gave them a lifetime in ten minutes. Words were fed into them. Time disappeared and they now Knew everything they needed to Know. They were hypnotized.

Next, they were fitted with their symbols, and everyone was happy.

Soon, the demand for the lovely ugly words and symbols increased to such a point that as the forests grew, many people were needed to maintain them. Some were employed to climb the trees and throw the words down to those below. They were then fed directly into the remainder of the Führer’s people, not to mention those who came back for more.

The people who climbed the trees were called word shakers.

The best word shakers were the ones who understood the true power of words. They were the ones who could climb the highest. One such word shaker was a small, skinny girl. She was renowned as the best word shaker of her region because she Knew how powerless a person could be WITHOUT words.

That’s why she could climb higher than anyone else. She had desire. She was hungry for them.

One day, however, she met a man who was despised by her homeland, even though he was born in it. They became good friends, and when the man was sick, the word shaker allowed a single teardrop to fall on his face. The tear was made of friendship—a single word—and it dried and became a seed, and when next the girl was in the forest, she planted that seed among the other trees. She watered it every day.

At first, there was nothing, but one afternoon, when she checked it after a day of word-shaking, a small sprout had shot up. She stared at it for a long time.

The tree grew every day, faster than everything else, till it was the tallest tree in the forest. Everyone came to look at it. They all whispered about it, and they waited . . . for the Fuhrer. Incensed, he immediately ordered the tree to be cut down. That was when the word shaker made her way through the crowd. She fell to her hands and Knees. “Please,” she cried, “you can’t cut it down.”

The Führer, however, was unmoved. He could not afford to make exceptions. As the word shaker was dragged away, he turned to his right-hand man and made a request. “Ax, please.”

At that moment, the word shaker twisted free. She ran. She boarded the tree, and even as the Führer hammered at the trunk with his ax, she climbed until she reached the highest of the branches. The voices and ax beats continued faintly on. Clouds walked by—like white monsters with gray hearts. Afraid but stubborn, the word shaker remained. She waited for the tree to fall.

But the tree would not move.

Many hours passed, and still, the Führer’s ax could not take a single bite out of the trunk. In a state nearing collapse, he ordered another man to continue.

Days passed.

Weeks took over.

A hundred and ninety-six soldiers could not make any impact on the word shaker’s tree.

“But how does she eat?” the people asked. “How does she sleep?”

What they didn’t Know was that other word shakers threw supplies across, and the girl climbed down to the lower branches to collect them.

It snowed. It rained. Seasons came and went. The word shaker remained.

When the last axman gave up, he called up to her. “Word shaker! You can come down now! There is no one who can defeat this tree!”

The word shaker, who could only just make out the man’s sentences, replied with a whisper. She handed it down through the branches. “No thank you,” she said, for she Knew that it was only herself who was holding the tree upright.

No one Knew how long it had taken, but one afternoon, a new axman walked into town. His bag looked too heavy for him. His eyes dragged. His feet drooped with exhaustion. “The tree,” he asked the people. “Where is the tree?”

An audience followed him, and when he arrived, clouds had covered the highest regions of the branches. The word shaker could hear the people calling out that a new axman had come to put an end to her vigil.

“She will not come down,” the people said, “for anyone.”

They did not Know who the axman was, and they did not Know that he was undeterred.

He opened his bag and pulled out something much smaller than an ax.

The people laughed. They said, “You can’t chop a tree down with an old hammer!”

The young man did not listen to them. He only looked through his bag for some nails. He placed three of them in his mouth and attempted to hammer a fourth one into the tree. The first branches were now extremely high and he estimated that he needed four nails to use as footholds to reach them.

“Look at this idiot,” roared one of the watching men. “No one else could chop it down with an ax, and this fool thinks he can do it with—”

The man fell silent.

The first nail entered the tree and was held steady after five blows. Then the second went in, and the young man started to climb.

By the fourth nail, he was up in the arms and continued on his way. He was tempted to call out as he did so, but he decided against it.

The climb seemed to last for miles. It took many hours for him to reach the final branches, and when he did, he found the word shaker asleep in her blankets and the clouds.

He watched her for many minutes. The warmth of the sun heated the cloudy rooftop. He reached down, touching her arm, and the word shaker woke up. She rubbed her eyes, and after a long study of his face, she spoke.

“Is it really you?”

Is it from your cheek, she thought, that I took the seed?

The man nodded.

His heart wobbled and he held tighter to the branches. “It is.”

Together, they stayed in the summit of the tree. They waited for the clouds to disappear, and when they did, they could see the rest of the forest.

“It wouldn’t stop growing,” she explained.

“But neither would this.” The young man looked at the branch that held his hand. He had a point.

When they had looked and talked enough, they made their way back down. They left the blankets and remaining food behind.

The people could not believe what they were seeing, and the moment the word shaker and the young man set foot in the world, the tree finally began to show the ax marks. Bruises appeared. Slits were made in the trunk and the earth began to shiver.

“It’s going to fall!” a young woman screamed. “The tree is going to fall!” She was right. The word shaker’s tree, in all its miles and miles of height, slowly began to tip. It moaned as it was sucked to the ground. The world shook, and when everything finally settled, the tree was laid out among the rest of the forest. It could never destroy all of it, but if nothing else, a different-colored path was carved through it.

The word shaker and the young man climbed up to the horizontal trunk. They navigated the branches and began to walk. When they looked back, they noticed that the majority of onlookers had started to return to their own places. In there. Out there. In the forest.

But as they walked on, they stopped several times, to listen. They thought they could hear voices and words behind them, on the word shaker’s tree.

******************************************************************

“Did you read it?” she asked, but she did not look at me. Her eyes were fixed to the words.

I nodded. “Many times.”

“Could you understand it?”

And at that point, there was a great pause.

A few cars drove by, each way. Their drivers were Hitlers and Hubermanns, and Maxes, killers, Dillers, and Steiners. . . .

I wanted to tell the book thief many things, about beauty and brutality. But what could I tell her about those things that she didn’t already know? I wanted to explain that I am constantly overestimating and underestimating the human race—that rarely do I ever simply estimate it. I wanted to ask her how the same thing could be so ugly and so glorious, and its words and stories so damning and brilliant.

None of those things, however, came out of my mouth.

All I was able to do was turn to Liesel Meminger and tell her the only truth I truly know. I said it to the book thief and I say it now to you.

A LAST NOTE FROM YOUR NARRATOR

I am haunted by humans.